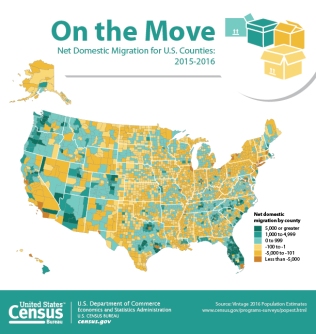

A recent New York Times op-ed (JD Vance, March 16, 2017) touched on many strands of my own research into population mobility and migration. First, the article also touched on the decline in migration rates over time, along with migration’s ability to concentrate highly skilled people in large cities at the expense of smaller towns and rural areas, potentially creating differences in long-term economic growth between places that have and don’t have highly skilled populations, with implications for such things as politics and the provision of services.

Second, it reminded me of much of my early research into the long distance migration of individuals and families in Canada and the United States. Much of this work was related to the concept of ‘return migration’, or individuals who return home after an initial migration. At the time, I often wrote that the return home was likely because of a ‘failed migration’ – a job that hadn’t materialized, was terminated, or wasn’t as good as expected, for example. But, as my research evolved, and I started to work with different data and alternative ways to look at migration, it became apparent that not all return migrations were the result of failure. In fact, many were planned returns: people returning home after they retired to a place they grew up or vacationed, returning home after a short work experience or contractual employment, or returning home to seek a different quality of life which could be rooted in the nature of small towns or family and friends. In fact, the research demonstrated that return migrations were planned in a large proportion of cases.

Return migrations remain an important and undeniable part of our own mobility. But the article also points to the depth of understanding and the added detail that can be obtained in listening to the stories of migrants and the details that can never be unearthed in statistical data collected by groups such as the US Census Bureau. As Kevin McHugh (2000, p. 75) wrote, “migration cannot be told solely in terms of abstract push–pull models nor neatly separated into ‘determinants’ and ‘consequences’, the sorts of divisions commonly found in analytical studies”. Although population geography has not fully embraced qualitative research as a way to understand migration, the article by Vance, and the work by McHugh and others points to its opportunities and importance.

Further Reading:

JD Vance, Why I’m Moving Home, The New York Times, 16 March 2017, p. A23. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/16/opinion/why-im-moving-home.html?smprod=nytcore-iphone&smid=nytcore-iphone-share

On the more academic side, see:

Kevin E. McHugh. (2000). Inside, outside, upside down, backward, forward, round and round: A case for ethnographic studies in migration. Progress in Human Geography. 24(1): 71-89.

Bruce Newbold and Martin Bell. (2001). Return and onwards migration in Canada and Australia: Evidence from fixed interval data. International Migration Review, 35(4):1157-1184.